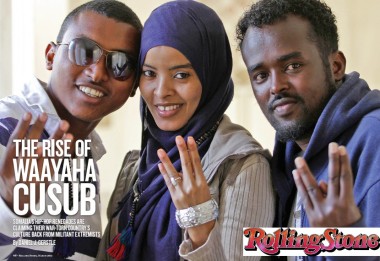

LITERARY | Somalia & Kenya: The Rise of Waayaha Cusub

SOMALIA & KENYA | DANIEL J. GERSTLE | MAY 2012

Originally published in Rolling Stone (Middle East edition)

Republished here November 2024

Shiine Akhyaar, the outspoken lead singer and manager of Somali hip-hop collective Waayaha Cusub, loves to share his political opinions, but rarely talks about his personal life. Today, though, he allows a brief, wordless moment as he grins at me through the video call screen over the newborn baby swaddled in his arms – his son Omar. His wife (and fellow vocalist) Falis Abdi, also one of the best-known faces and voices in modern Somali music, slips through the room, modestly focused on their other child, two-year-old Sirad.

It’s been three years since Somali extremists ordered Akhyaar and Abdi – who live in Nairobi, the capital of Somalia’s neighbor, Kenya – to stop making music. The entire collective was threatened, and the militants eventually broke into Akhyaar’s home, then shot him several times.

But Akhyaar remains defiant. Indeed, he makes no attempt to hide his group’s plan to bring live music back to war-ravaged southern Somalia and one of the world’s most dangerous cities, Mogadishu. He tells Rolling Stone, “I want them all to know that I’m coming.”

Al Shabab, a radical Islamic militia backed by political force Hezb-ul-Islam, Al Qaeda, and other extremists, have controlled most of southern Somalia since 2006. They claim to be saving the country from warlords and depravity. They do this not only by limiting foreign aid, conscripting youth, and encouraging the assassination and bombing of their enemies, but also by outlawing any music and culture not directly promoting their Islamic views.

When Waayaha Cusub was founded in the mid-2000s, they made their name singing about friendship, romance and life in exile. But the politics of music – and the politics of politics – in their home country have led the group to focus on the fight against extremism on their latest albums.

“Al Shabab are bad people,” says Akhyaar. “They shot me and they are ruining the country. Our goal is to spread our message of peace and to tell people to say no to them.”

Waayaha Cusub, whose name means, “New Era,” features not only Akhyaar and Abdi, but also tough rapper Lixle Muhuyadin, stylish tenor Dikriyow Abdi, angel-faced Ahmed Yareh, and a rotation of six other cameo singers. When they perform, they collaborate with bands like Kenya’s Afrobeat stars, Afro-Simba. Waayaha Cusub are already known in global media for challenging Somalia’s warlords, pirates, and extremists (and across Africa and the Middle East as the group that pioneered a successful hybrid of African Horn music with global genres including hip-hop, reggae, and even Hindi pop).

But Waayaha Cusub’s new commitment to lead the return of live modern music to Somalia’s frontline areas is building a legacy far beyond hip-hop diplomacy. They are rapidly conquering entertainment territory where global stars like Bob Geldoff, Roger Waters, Peter Gabriel, and even Somali-born K’naan may have failed.

Violence- and hunger-stricken Africans have already seen wealthy foreign superstars holding galas to ask Westerners to donate money. And while their efforts have saved countless lives, authorities on humanitarianism ranging from the One campaign to global aid expert Alex de Waal still find it difficult to prove whether such galas have actually reduced the causes of famine and conflict as opposed to providing only quick fixes.

But Waayaha Cusub’s mere arrival on a remote desert airstrip in their last tour to northern Somalia raised local morale so much that extremists actually complained in their sermons that the band’s influence was making it harder for them to conquer the country.

Waayaha Cusub are demonstrating how a local band singing directly to at-risk would-be fighters and youth inside the community in their own language, rallying them to peacefully resist armed gangs, could be the most effective way to pursue positive change through music in war and famine in Africa.

“With rhythm, melody, and harmony, music is expression for all aspects of human life,” says Salah Donyale, a U.S.-based Somali pop music producer and songwriter, reflecting on recent attacks and threats against musicians in the Horn of Africa. “And yet, these expressions make conflict with those people in power such as governments and big corporations.”

“Waayaha Cusub is a contemporary Somali band with blend of hip hop,” Donyale says. “They are a political but patriotic band that promotes peace and prosperity for all Somalis and they were one of the first to condemn the punitive actions of Al Shabab. They also address taboo subjects such as Aids, sex and drugs.” Their music, Donyale explains, is very influential in a region where many youth are looking for positive or hip role models and find few who are both.

Donyale writes and produces many of the top Somali pop songs coming out of North America, including “Wax Barasho,” his latest Afrohop hit, written about staying in school and sung by Mohamed Yare and Ilka Case. Somali music, Donyale says, originated in the storytelling tradition of the nomadic camel-herding communities of the region around the Gulf of Aden, then evolved rapidly as Sufi scholars, trained in Arabia and Yemen, spread the word of Islam.

After independence from Italy and Great Britain in 1961, Somalia’s music industry grew rapidly. President Siad Barre, though accused by many of fomenting ethnic tension, endowed the capitol, Mogadishu with programs supporting national arts. The National Thater would become home to Waaberi, a label-like collective which introduced the world to stars like Hasan Samatar, known for his ballads, and Maryam Mursal, whose song “Somali Udiida Ceeb” was the first Somali song to circulate globally, winning the attention of Peter Gabriel who signed her to Real World Records.

Today, Waaberi alum Abdi Shire Jama is the most widely known Somali singer to promote politics through music. His old-school group, Qaylodhaan, singing over pre-recorded synthesizers, are the older generation’s equivalent of Waayaha Cusub.

By 1988, when the Barre regime started bombing rebel strongholds in the northwest, triggering the current civil war which swept into the capital in 1991, musicians including Mursal, Samatar, and Jama, fled. New stars are now recreating the Somali music industry in exile. K’naan took off in Toronto. Aar Manta and newcomer Mohamed Ameen are rising in London. Nearly everyone else – Salah Donyale, Jaabir Jarkadood, Abbas Hirad, and many others – cultivate their music via wintery Minneapolis.

Meanwhile, ultra-conservatives, who had gone instead to the Gulf seeking religious study, returned to Somalia, bringing back the idea that Somalia’s musical storytelling tradition, now weakened, should be erased.

Akhyaar, who grew up in the central town of Dhusamareeb, witnessed this dramatic radicalization of Somalia up close. Not wanting to abandon his country entirely, he fled south to Kenya where he connected with fellow newcomers to music.

Falis Abdi, facing the same changes in the southern port city of Kismayo, took the same route. Soon enough they met Lixle, Dikriyow, Ahmed, Burhan, and others and created their new collective; they shared Waaberi’s format, but with an entirely new genre of music. They created Scratch Records (through which they’ve released six albums) and Scratch Filmz to produce their videos.

Akhyaar and Abdi met as friends, but soon revealed their romance and marriage in Nairobi to fans through lyrics and music videos. Conservatives hissed at Abdi’s early sultry dance in performances and videos, even those songs in which she pledged herself to her new husband. Meanwhile, thousands of fans, especially after an unproven rumor surfaced that female singer and friend Ikraan Araale may have had a crush on Akhyaar, rallied behind Abdi and continue to celebrate her as that rare combination of hip, loyal, and moral, no matter how she dances.

Their videos have invited heated criticism online. Even a seemingly innocuous track like “Allaa Weyn” (God Created) – which features the group’s men and women dressed in Nairobi fashion dancing together to a song that bemoans mankind’s cruelty to mankind in a beautiful world – is described as “SHOCKING” and “UN-ISLAMIC.”

The group also has plenty of defenders. “This talented, smart, intelligent crew are setting a very good example for the Somali people,” writes one in the comments to another song, “Nabad” (Peace). “I love what they are doing. Guys, keep your heads up. Insha’Allah, one day Somalia will be at peace.”

In 2008, radicals aiming to cleanse Mogadishu of such cultural liberalism killed Waaberi’s Aden Hasan Salad, Abdulkadir Adow Ali, and Omar Nur Basharah in separate attacks. Their allies in Nairobi threatened Waayaha Cusub, ordered them to stop making music, and broke into Akhyaar’s home, guns blasting.

Shot in the hip and the arm, Akhyaar survived with an even tighter commitment to his quest to bring modern music back to Somalia. Though he and Falis are reluctant to talk in detail about the attack and the continuing threats against them, Akhyaar has no problem showing people he trusts the bullet wounds still visible in his side and leg with a look of defiant pride.

When global star K’naan bravely returned to Mogadishu in 2009 it was a dangerous time for any musician to do so. Music lovers took a breath of hope from his visit, but he was there so briefly the rebels hardly noticed. Global Broadcasting Company radio producer, Mohamed Ayaanle, remembers the furious debate over music and radio in the country during this time.

“Al Shabab and Hezb-ul-Islam both ordered our radio station to close twice,” Ayaanle says. “The first time, they banned all the radio and TV stations in the capitol from playing songs to the population. The second time, they banned any type of music at all. Hezb-ul-Islam said they would kill people at any radio station playing songs.”

When asked whether a band like Waayaha Cusub should cancel plans to return to Mogadishu just for a couple days of performance, Ayaanle’s emphasized that their ability to move around, rehearse, and breathe would be extremely limited.

“If you are a musician going back to Mogadishu you have to stay on the government side, in the territory they control. But you have to have so many troops for your security, you can’t live.”

“Waayaha Cusub,” says Towfik Elmi, a California-based scholar, “has carved a good reputation out of Somalia’s chaos and political crisis. They use powerful Somali lyrics and a rich timbre sound to warn uninformed youth about the bait of that imported ideology. They will be welcomed by Somalis in those areas liberated from Al Shabab by the Somali government and Kenyan Army.”

Akhyaar and his band wrote “Yaabka Al Shabab” (Refuse the Youth Militia), one of their most popular songs to date, for their tours across the Horn of Africa this past year. They light the fuse with an Afrobeat rhythm and bass, carpet it with Shiine and Lixle chanting, “Shocked, shocked/ Shocked, shocked” And then Falis’s soprano Hindi-pop melody rings out a chorus of call and response.

“Who is behind this trail of destruction?” she sings. “Al Shabab!” chant the men. “Who committed this killing of a people?” “Al Shabab!” “I heard this story while filling with scorn for you,” she adds, handing off to Shiine and Lixle who take turns rapping: “They galvanize the average ignorant person on the street for their wicked cause/Shocked Shocked!/One who professes to be Muslim yet wields machetes.”

“History reveals that you may censor some kinds of song,” says the U.S.-based producer Donyale. “But you cannot ban music. You’re violating national conventions and human rights. As long as people can talk, they will sing. And as long as people can walk or even move, they will dance.”

“Music, they can’t stop it,” Akhyaar says. “Music is an international language. If you are English, or Kenyan, or Ethiopian, or Somali, or Afghan, music has the same purpose. Everybody likes music. Al Shabab can’t stop it.”

******