LITERARY | Afghanistan: Amplifiers in Kabul

December 2011 | Culture | Daniel J. Gerstle, images by David Gill

Humanitarian Bazaar Magazine, originally published in Rolling Stone: Middle East; reprinted with permission.

We’re cutting through the black, dusty night searching for a rock party in a secret underground bunker in Kabul, Afghanistan. Crossing the intersection past a police checkpoint and heading down an empty street, we hear a low, throbbing growl emanate from the basement of an apartment building. The bass and drums softly pulsating in the shadows of a silent war zone are enough to drop blood pressure, hasten respiration, and spark the bitter taste of adrenaline.

Descending hidden stairs into smoky, red light we are swallowed by the thunder of amplified guitar in Hoodies, the city’s first hard-rock club. Inside, people are moshing to Afghan rock band White Page’s performance of System of a Down’s “Toxicity.” Someone slams me so hard I fly across the room into a couple of journos and split my shoe down the seam.

Looking up before slamming back, I find the tufted beard of Qasem Foushanji, the tall singer, bassist, and modern artist who, along with his drummer brother Pedram, and guitarist friend, Qais Shaghasi, are quickly becoming leaders in Afghanistan’s first true counter-culture movement.

Qasem, with his long arms and top-heavy hair, has that way of looking both intimidating and boyish at the same time. His brother, Pedram, moshing beside him, is a cold steel intellectual with surgical wit, an Abe Lincoln beard, and knuckles taped from beating the shine off cymbals and snare. Shaghasi, standing on the edge of the crowd just drinking in the music, has the quiet stare of someone who’s trying to figure out how to win a girl back from a longtime enemy.

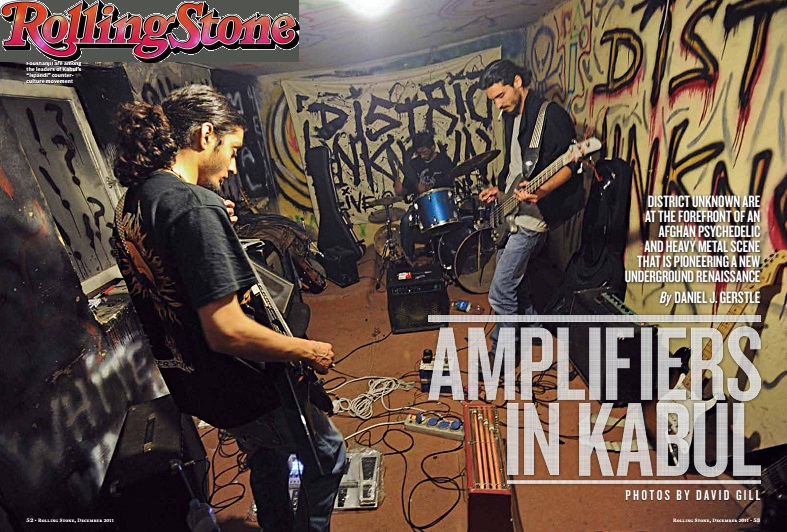

Performing together they are District Unknown, the country’s first heavy metal band and pioneers of “psychedelic metal.” They want nothing more than to produce the loudest, meanest music ever performed in Afghanistan.

Tonight they are banging their heads with their good friends, the younger, newer rock band, White Page. Singer Raby Adib descends from the stage into the milieu to share vocals with Qasem, who grabs the mic, turns into a wolf, and lets out a jaded “Somewhere, between the sacred silence and sleep/Disorder, disorder, disorrrrrrder.”

For District Unknown, music has been a source of catharsis and meaning beyond anything else in their native war zone. In a city so traumatized and conservative that cemeteries have outgrown parks, where hash smoke fills alleyways and alcohol is forbidden, where hanging out with a girl can destroy her reputation, and where music was banned under the previous government, there is nothing more exhilarating than pounding that tension out in rehearsal, dreaming of performing at an underground club filled with a screaming, co-ed mob of metal heads.

But Kabul is surrounded by close-minded fathers, radicals, and rebels fighting to take the country back from moderates and re-install nationwide bans on music and counter-culture. Ultraconservative Taliban rebels and their allies have been blamed for September’s music store bombing in nearby Peshawar and 2010’s bombing of a pop concert in Herat. They want to keep not only rock musicians, but all musicians, free-thinking writers, abstract painters, punks, skaters, and street artists silenced or out of the country.

It’s September and around fifty of Kabul’s hard-rock musicians, metal heads, artists, and bloggers have gathered in Hoodies every night this week along with foreign journalists and aid workers to celebrate Sound Central, the first Afghan rock festival in 35 years and – since every event is announced secretly through texts, like a rave – the world’s first “stealth” music festival.

Sound Central and Hoodies are the brainchildren of Australian filmmaker and local rock Godfather Travis Beard. The club, with five surprise concerts this week alone, is quickly becoming a rallying point for those who wish to deny the war any power over their nights. With the crazies looming in the hills around the city having just attacked the NATO compound a week earlier, some half-expect the police or a suicide attacker to break into the club – and many would probably welcome a raid.

Qasem grins devilishly. I do my best to slam him back into the fray before getting an elbow in the eye from someone else. He laughs, then slams Pedram into yet another victim of the mosh. Tonight is District Unknown’s night to let go and support Adib and their other friends in White Page. Tomorrow District Unknown will take the stage themselves, performing publicly for the first time without wearing masks.

Months before the festival, an ultra-conservative student found District Unknown’s Facebook page and sent them a stern warning that they should stop making modern music. Accusers had constructed a flammable lie: that the band had been receiving funds from Westerners to tempt the city’s youth – and girls in particular – toward sin. Fearing more false rumors, if not an actual attack, Pedram and Qasem went for help to state security.

They explained they were not only peaceful but pious, only to find that the government, too, had been watching the band. Not sure what else to do to protect themselves, the band took a page from their metal heroes, Slipknot, and decided to wear white masks on stage.

Within weeks of masking themselves, it became apparent that journalists and enemies alike already knew who they were. Together with fellow Afghan groups White Page and Face Off, blues-rock band Morcha, indie-rockers Kabul Dreams, expatriate music mentors, and leagues of local headbangers, artists, street taggers, and bloggers, District Unknown were beginning to see themselves as the frontline of Kabul’s counter-culture movement.

With tomorrow’s Sound Central festival concert as their opening salvo, they aim to claim a beachhead for freedom of expression in one of the most conservative and violent cities in the world. So the time has come to take a stand: either stop performing, or take off their masks.

The brothers have started to call the new movement “ispandi,” after those street urchins crowding traffic grids in the city who cast spells of protection on strangers with the smoke of heated flower seeds. Qasem says they considered Ispandi as a band name before settling on District Unknown. Like the actual ispandi kids, who offer blessings to complete strangers while being treated like lepers, the counter-culture musicians and artists offer powerful messages of hope but are treated like unrepentant sinners.

“The smoke,” Qasem explains, “is said to take away bad things or danger, to bless a person or a thing. The ispandis are very innocent and so poor they have to work that way to provide money for home. Ispandis reflect a tragic side of Afghan society, which is vast. As a band name, it would sound kind of funny to many Afghan people, and very low class, but I am sure many of them would also like it because it shows sympathy towards those kids, towards that part of society.”

Qasem, as an abstract painter whose work – like his lyrics – is saturated in blacks and grays, or contrastingly in reds and yellows, believes music and art are intertwined, particularly in a people’s attempt to re-emerge after a prolonged national tragedy like Afghanistan’s latest war. He believes musicians and artists are compelled to find meaning in what’s happening around them, not simply escape it. This is the critical passion that sets District Unknown and their peers apart from Afghanistan’s other musicians and artists.

“Being unrealistic and feeling surrealistic in a country like Afghanistan,” Qasem tells me, “doesn’t help the flavor of music. One should not sing about going out for a coffee with a fucking non-existent girlfriend. We’ve got blood and bodies, tragedy, and despair here. We have to stick to what is real, and seek a solution.”

District Unknown and the Movement they represent converged this past summer thanks to the cultural glue of Beard – the Australian punk – and his collection of Kabul rock friends. Beard, a photographer, biker, graffiti artist, rock guitarist, and filmmaker known to free-thinkers all over Central Asia, is quickly becoming Kabul’s Malcolm McLaren. He first raised the profile of the Afghan rock scene when he joined White City, a rock band made up of expatriate journalists and aid workers.

When White City – fronted by Ru Owen, a tall and sharp-witted singer-bassist, backed by Beard on guitar and Andronik Stefansson, a bright and gregarious drummer – began writing original progressive punk songs like “Perfect 10” and “Silver Hyena,” Beard found himself the idol of a number of Afghan rock fans, especially those who wanted to bring hard rock back to the country.

Beard began mentoring, and documenting the rise of, Kabul Dreams. Fronted by singer-guitarist Sulyman Qardosh, the band write safe songs with a California sound. Soon enough, they gained popularity and began planning a tour outside the country. For Beard, Kabul Dreams was just the beginning. He wanted to nurture the next step in that progression, Kabul’s tortured underbelly: heavy metal.

Ever since arriving from Iran, where the Foushanjis had sought refuge during the war, Pedram couldn’t wait to get his hands and feet bloodied pounding heavy metal on a drum kit. His brother Qasem, who had been painting abstract art, also loved metal. The two had grown up learning about the Afghan superstar, Ahmad Zahir, who wooed the entire region with a hybrid of pop-rock with classical Afghan vocal stylings and who was allegedly assassinated in 1979, although the government claimed he had died in a car crash.

The brothers had been blasting Opeth, Metallica, and other metal bands on their headphones, and both knew there was something powerful about performing the music, not just listening to it. Qasem loved to quote lyrics from bands including their heroes, Slipknot, on his Facebook page, believing lines like “Who the fuck am I to criticize your twisted state of mind… /Fuck this shit, I’m sick of it/You’re going down/This is a war,” fit the mood of young Afghans perfectly.

When the brothers saw White City perform, Pedram was quick to approach Beard to ask where they might be able to practice. The guitarist took one look at them and knew they’d work well with two brooding guitarists named Qais Shaghasi and Lemar Saifulla.

Saifulla had an impressive presence and had mastered the attitude of Anathema, Opeth, and Zahir. After a quick jam, Saifulla took vocals and rhythm guitar, Shaghasi took lead guitar, Qasem discovered bass, and Pedram was finally drumming with a raw, but serious, metal outfit. Beard mentored the group, bringing in his expat friend Archie Gallet to give pointers on bringing the right kinds of noise out of their instruments.

“They turned up at the door one day, all rock-starred up, long hair and black T-shirts, saying they were a metal band,” remembers Gallet. “But they didn’t know how to play and did not have a single instrument. They trashed our gear for a few months, and then went live.”

“We were illiterate in music but we started a band,” says Pedram about the early days of District Unknown. “We had our first gig at our home, a house party that my youngest uncle threw and then the journey of our band officially started.”

“The band helped me become what I am,” says Saifulla – who has since moved with his family to Turkey. “When Qais and I were learning instruments we intended to learn metal, specifically, so we were, with the Foushanji brothers, the first headbangers making metal at that time.”

When Saifulla’s family moved to Turkey with him in tow, it was only natural for Qasem to step in and take his place as frontman. Although Qasem was still figuring out his vocal style, he was a natural-born ruler of the stage.

In District Unknown’s first recorded track, “My Nightmares,” sung by Saifulla and Qasem, the quartet reveal their hopeful yet bloody realism. “For us,” they sing in Dari. “For us, there’s no Arghawan [a purple flower, a symbol of youth, hope, and peace]/Not even in our dreams/Why? For us/Come oh brother/Plant the seed of Arghawan over my palms/War with each other/Away from each other/Why? At last, my hope will turn into mourning/Why?”

Beard was psyched to get in the studio with them, kick their asses, and see how loud they could push the amplifiers. One night, I catch Beard scolding them for considering bowing out on a radio interview. “Fucking get your instruments and get down there,” Beard told them. He has somehow moved beyond the mentor role, leapfrogged the role of manager, and instead become their strict uncle.

Gallet, like Beard, was a tough mentor, telling the band it wasn’t good enough just to be loud and to love what they were doing, insisting they improve as musicians. Regardless, he couldn’t help but fall in love with what they were becoming. “District Unknown has a very advanced image, message and attitude, and they are really into experimenting with some weird alternative music stuff,” he says. “It will take them a while to get there, but eventually they will blow everybody up.”

The Kabul counter-culture movement is only just beginning to spark, but it’s already attracting new blood. Beard and Gallet joined forces with Afghan impresario Humayun Zadran this year to produce incubation projects for Kabul’s newest rock musicians and street artists.

Beard, already playing with White City and a co-founder of the promising Skateistan project which teaches Afghan youth how to board a half-pipe, also led the formation of Combat Comms – an umbrella group for both crisis and music media.

With the latter, he began filming the early days of Kabul’s rock scene, as well as the Kabul Knight’s motorbike club. He also nailed down funding for a project called Wallords where punk spray taggers including Beard and Qasem teach youth how to beautify Kabul’s alleys with spray-painted murals, cartoons, and tags. Unknown in Kabul, street art has actually been welcomed in many circles, not seen as vandalism at all.

Zadran – a huge Led Zeppelin fan – wanted to shape something new with Kabul’s emerging talent. Partnering with Gallet and Beard, Zadran and musician Robin Ryczek created Sound Studies to forge alliances between the rebellious rockers and some of the country’s classical musicians. Then, with support from Gallet, Zadran and Ryczek built The Floating Room, the country’s first studio devoted to hard rock and alternative music, where rockers had a home and rock/classical hybrids could be done right.

“I see it as a lab where they can come, record and learn,” says Gallet. “And we’ll release bootlegs, punk style. We have the buzz already, and when the kids come with a good track, we’ll make them fuckin’ huge.”

Whether they want – or can afford – to be huge is another matter. Music is a risky business in Afghanistan. Hojat Hameed, the guitarist in White Page, says his involvement in the band has caused problems at home.

“I spent six years in music school without telling my father,” he tells me. “He’s from a Pashtun tribe and his family is kind of conservative. They are totally against music. When my father found out – after six years – that I had been studying music, he was so upset that he asked me to not speak with him anymore. He nearly threw me out of the house.”

The radicals, Hameed explains, “are not against only rock music. They are against music in general. But I love being with music. Music is a major part of my life.”

With Kabul’s musicians, painters, and skaters finally meeting one another and collaborating on so many new projects, word began to spread. Soon, Afghan musicians and artists in the diaspora, as well as performers on the world stage, began to reach out. One of the first was Afghan-American rock singer, Fereshta, based in Los Angeles, whose family fled Afghanistan at the beginning of the war. She wanted to offer advice to the bands when she heard they were beginning to perform in public after three rockless decades.

“These bands have to do a lot of the work themselves,” Fereshta says. “On the bright side, the current Afghan rock scene – like the punk and thrash metal scenes of the Eighties – has its benefits, too, with sovereignty being one of them. Because there are no suits in the room telling you what to do, it becomes more about your art and your creative expression, not someone else’s bottom line.”

Post-punk performer Zohra Atash of the Brooklyn-based band, Religious to Damn, and Los Angeles-based psychadelic rocker, Ariana Delawari – two very different singers from the Afghan diaspora – had been crafting their concerts, music, and videos for several years before discovering not only the new Afghan counter-culture movement but also each other.

Now, like Fereshta, they are trying to figure out how to ensure it will be safe enough to perform and produce as women alongside the almost exclusively male Kabul-based musicians and artists.

“At the risk of sounding arrogant,” Atash reflects. “I didn’t know there were any other Afghans in ‘rock’ bands besides me, let alone an entire scene. I think it’s fantastic. I would have been thrilled had I known any of the musicians out there played more than the standard wedding dance-party shit I call ‘Yamaha-wave.’”

Delawari, whose first album, Lion of Panjshir, was recorded in Afghanistan and mixed in the U.S. by filmmaker David Lynch, has just completed a feature documentary about how she returned to Afghanistan to reconnect with her family while making alternative music.

“I think that they should be bold and honest,” she says of Kabul’s young artists. “They should do it in numbers, so that it’s a movement. People sense fear. If you approach life fearlessly the monsters of society dissolve. If we open our hearts and jump without a net, all kinds of miracles can happen.”

Atash admits that any form of counter-culture in a place as conservative as Afghanistan could be considered an act of rebellion, making it potentially risky.

“I would like to go to Afghanistan someday, in the distant future, to see my Grammy’s grave, to buy beautiful handmade goods, to eat delicious food … but to play there? I’m actually sort of stunned that I never once entertained the idea,” she says. “Not even once. It’s not a matter of not wanting to perform there. It’s more an issue of not being able to go back there. Not until there are some serious changes made. It’s upsetting to talk about. I think being able to play music is a basic human right they should fight for, tooth and nail.”

“In shops, hotels, vehicles and rickshaws cassettes and music are prohibited,” read a decree from the Taliban’s religious police during their rule from 1994 to 2001, according to Girardet and Walter’s Afghanistan: Essential Field Guide. “If any music cassette [is] found in a shop, the shopkeeper [will] be imprisoned and the shop locked.”

There are plenty who still believe this law should be in force. On the “Afghan Culture” Facebook group, the host posted a video from Sound Central, asking people what they thought. High fives included: “A very progressive step!” and “What a way to play music and show the conservatives and religious extremists that music is back and there’s nothing they can do about it.”

But even tech-savvy Afghan conservatives couldn’t help but bash the movement. “One heart cannot love music and Quran at the same time,” wrote one correspondent. Another wrote, “I’m shocked that you ‘Muslims’ are avoiding your imam for something worthless shame on you.” “I think that was a comedian show,” wrote a third, “not a concert ha ha ha ha ha.” And the kicker: “I will smash any instrument I see.”

There has never been a beatnik, punk, or hippy movement among Afghans, so the Foushanjis and their peers in the new counter-culture have no true precedents to learn from. The closest contemporary case is that of the Iraqi metal band, Acrassicauda, who recently connected with District Unknown online.

Acrassicauda – whose story went global via the VICE documentary, Heavy Metal in Baghdad – bravely shredded in their native city during the Iraq War. But after religious zealots bombed their practice space, the thrashers moved to the U.S.

Testament guitarist Alex Skolnick, who also offered words of hope to the Afghan artists during Sound Central, was just one global performer who helped ease Acrassicauda’s transition from the Iraq war zone to the U.S. rock circuit.

“I’d expected these guys to be weary, withdrawn and war-torn,” Skolnick says about Acrassicauda, in the context of the new bands risking their lives for music in Afghanistan. “But that couldn’t have been farther from the truth. They were warm, friendly and full of humor. I’d also thought it would take time to get them to warm up to us, being from America, a nation which had launched a full-scale invasion of their country, for reasons that they, and even we, couldn’t understand. But these guys held no prejudgements – unlike so many in the U.S. who’d be quick to condemn Iraqis as ‘terrorists’ – and went against all the stereotypes.”

When Pedram and Qasem finally get the chance to talk with Acrassicauda’s drummer Marwan Hussein by Skype at a Sound Central workshop, they lay out District Unknown’s mission statement. “What we’re writing about,” Pedram explains, “it’s fact. We use what happens here.” “Somebody needs to be on the frontline,” Qasem adds.

“Double horns for you,” Hussein replies. “I respect what you guys are doing, even with your faces hidden. You’re putting your lives and your families’ lives in danger, for music.”

Mohamed Jawad, an Afghan political blogger, recently wrote about the importance of the burgeoning music scene for his country’s future. “Rock and alternative music fans have realized that music is something for the soul and they are here to have fun in spite of the risks. We have had so much war in this country, rock music is something fun that you can open up to and be yourself. The audience of that music is afraid of the threats but [they] appear at the concerts because they want to have a good time no matter what.”

As for the musicians, Jawad continued, “They are people who said, ‘To hell with it. We will do what we want no matter what the conservatives say.’ They are aware of the danger, but they would rather face it than hide behind a curtain of lies.”

“Numb, shattered, hurt, cryıng, and opening up,” Saifulla recalls, about writing music amidst Kabul’s nerve-shredding tension. “It’s never-ending; that’s the truth. What we are screaming about can never end and it’s only getting worse day after day. It’s all burning and the fragments make us speak loud with rage.”

That next night, the Hoodies underground rock bunker party opens with Beard on the mic. “We want this to be an alternative scene so get fucked up on drugs and vomit in the corner, OK?” Cheers erupt.

Qasem enters the red light of the stage, without mask, and pulls on his five-string bass. Pedram hops onto the stool behind the drum kit. Shaghasi plugs in his guitar. And their friend Naseer joins in on keyboard. They blast the crowd with their opening song, “My Nightmares,” and then Qasem speaks his mind.

“We decided today not to wear our masks,” he says. “We just said, ‘Fuck it. We are what we are.’ We’re not the only band like this. If anyone is going to say shit, just say it to my face.”

And they play. Their latest song, “My Dying Bride,” which laments a NATO attack going awry during a wedding party, begins with Shaghasi pulling a long, low E-string bend. Then Pedram and Qasem come in together with a growing roar like a B-52 taking off. This is the dream come to life. Fans in the audience who have never been to a concert before are now seeing their friends and allies, surrounded by enemies, creating a new chapter in Afghanistan’s cultural history.

“You’re inspired by your surroundings and the people around you,” John Cale once told Rolling Stone, reflecting on the Velvet Underground’s role in America’s cultural history. “You may not even know them, but you’re inspired by the singularity of purpose. To break things down. To smash things.”

Speaking for District Unknown and the ispandi movement of Afghanistan, Lemar tells me, “Every act has its own place and every word has its own situation and time. In my opinion, all these brutal and enraged genres of the music world are the best weapon in my country. Smooth and blank, it hits you right where it hurts. And the pain will wake anyone from their deep winter sleep.”

District Unknown, and others, performed safely to small but fascinated crowds over three weeks of Sound Central, and the band have scheduled more shows at expat restaurants and friends’ houses for this winter. Their sound is evolving from slowed-down Slipknot metal to more of a “Paranoid”-era Black Sabbath rock.

Lester Bangs once wrote that Black Sabbath, in the face of mothers’ fears of evil intentions, were actually “the first Catholic rock band.” Sabbath’s deadly power, boiling up in songs like “War Pigs” and “Electric Funeral,” was a badass, macho kind of peacenik brotherhood. Young men full of balls and brawn, who might otherwise have grabbed a rifle and run into battle, were seduced by music about bombs and battles, which ultimately convinced them of the errors of war.

Sabbath’s metal, and the music of bands like Slipknot and System of a Down, is, in fact, a threat to the power of angry fathers. It gives young men in crisis the chance to be masculine and aggressive without having to be blindly obedient or violent.

District Unknown and their allies have survived, but are still threatened by, one of the longest and most brutal wars of our time. So it is fitting they have snatched up the banner of anti-war metal. The alternative is far more of a danger to society, despite what the authorities may say.

Rolling Stone Magazine

Humanitarianbazaar.org